By Sarah Brown

Lebanon Local

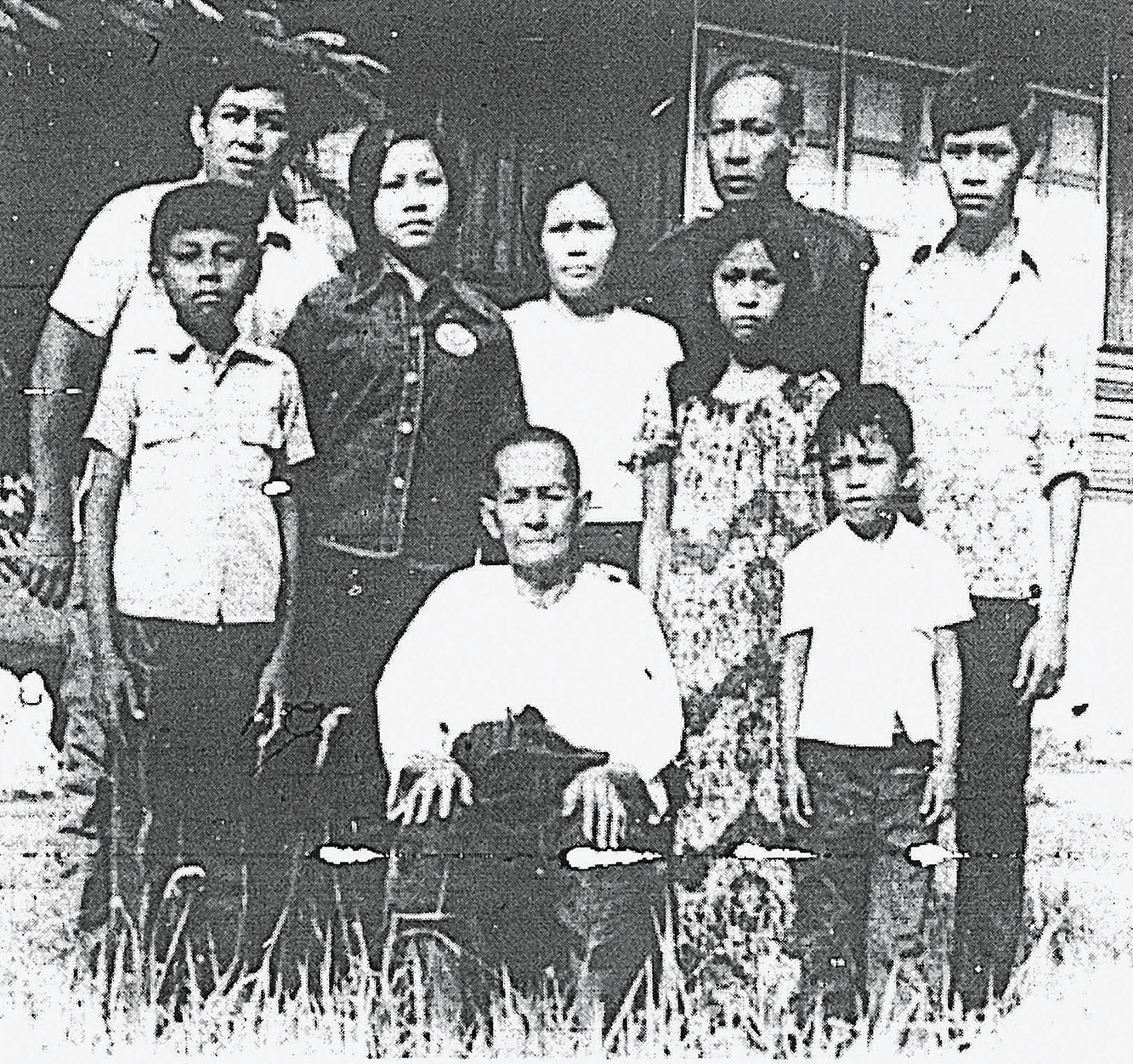

*This online version of the story has been edited Nov. 18 to correctly identify the head of the Mao family as Chhay Mao, not Chhrouk Mao. Also, the featured photo was identified as having been taken in Siem Reap, but was actually taken at a refugee camp in Thailand.

As smoke from nearby fires rolled over her Hillsboro home this past summer, Kanchana Mam was reminded of an even more terrifying time in her life 45 years ago – in Cambodia.

She was 16 when she narrowly escaped the threat of death at the hands of the Khmer Rouge. Her father, a politician, had the foresight to plan an escape into Thailand just two weeks before the insurgents overtook the capital city of Phnom Penh.

They and two other families of refugees from Southeast Asia found themselves on the other side of the world in 1975, in a little Oregon town called Lebanon. They were brought here under a refugee resettlement program, with sponsorship from the local Bethlehem Lutheran and Mennonite Churches.

A number of other local churches also assisted with the program: Our Saviour’s Lutheran, First United Methodist, First United Presbyterian, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and Sweet Home’s Fir Lawn Lutheran.

The brutal Khmer Rouge regime, led by Marxist leader Pol Pot, was in power from 1975-79, and claimed the lives of some 2 million people. The Khmer Rouge’s goal was to take Cambodia back to an agrarian society such as existed in the Middle Ages, forcing millions of people from the cities to work on communal farms in the countryside.

The brutal Khmer Rouge regime, led by Marxist leader Pol Pot, was in power from 1975-79, and claimed the lives of some 2 million people. The Khmer Rouge’s goal was to take Cambodia back to an agrarian society such as existed in the Middle Ages, forcing millions of people from the cities to work on communal farms in the countryside.

Chhiet Mao, another refugee to Lebanon, would say the tipping point that led to the infamous “Killing Fields” of Cambodia was when the United States bombed the Ho Chi Minh trail in his country in 1969.

The numbers of the communist-led Khmer Rouge grew, bombing their way through the forested curtains of Cambodia until reaching Phnom Penh, the capital, in 1975.

“Life was just horrible; lots of guns, bombs and rockets,” Kanchana said. “Our home (in Siem Reap) was bombed just one day after we escaped.”

Her family made it into Thailand the day following the communist takeover of Phnom Penh. Six months later, nine individuals of the Mam family, including Kanchana’s siblings, father, uncle, cousins and grandmother, arrived in Lebanon, in October 1975. Arriving with them was another family, the Kylys, who also fled to Thailand from Laos.

“It was one of those stories where (my parents) went at the dead of the night and sort of just pretended that they were Thai,” said DeL’Aurore Kyly, who was 1 year old when she arrived in Lebanon with her parents.

About two months later, a third family arrived, Chhay Mao with his daughter, Nouma, and son, Chhiet.

The refugees and their children, now American citizens, recalled those last days in Cambodia and their first experiences living in the United States. They are now grown, with their own families, and some have even returned to Cambodia to visit or help rebuild the country they left behind.

The Mam family

Photo courtesy of Sakal Mam

After 20 years serving in his country’s military, Sarath Mam became a congressman for the new Republic of Cambodia in the early 1970s. His brother, Khon Mam, also was a military officer. Those positions put them at risk for exe-cution by the Khmer Rouge who would take over in 1975.

“Due to our status in society there, we’re in grave danger. The Khmer Rouge will not tolerate any high ranking military or politicians,” said Viphea Mam, Khon’s son. “So my uncle has already decide that if the country fell to the Khmer Rouge, we will get out, we will leave Cambodia, and we will go directly to Thailand because he has connection, he knows people there.”

By April 1975, as the Khmer Rouge advanced on Phnom Penh, where the Mam families were staying, Sarath found a plane and evacuated some of his family out of the city to the northernmost province, Oddar Meanchey.

Viphea and his brother, Achharya, were living with their uncle Sarath at the time to be closer to school, so they boarded the plane for Thailand. His father was also with them, but his mother, three sisters and another brother were left behind.

“My mom waiting for my dad, my uncle, you know, everybody together, but we had no hear, no connection, no anything. We don’t know what’s going on,” said Chhorvy Hoy, one of Viphea’s sisters.

Viphea remembers boarding the plane – he recalls it was maybe a DC-3 or DC-5 – which had no seats and was used to carry ammunition, and he recalls flipping backward off an ammunition case when the plane took off. He was 11 years old.

Viphea lived the first part of his life with war and bombings. Most of it was distant from him, but he did witness a bomb blow up a marketplace in front of him, spreading body parts and dispersing crowds.

Despite that, all he knew was they were moving up north and he would get an extended vacation from school. He didn’t understand they were escaping something terrible, he said.

They entered Thailand on April 18, and landed at Ft. Chaffee, Ark. in October. Less than a week later, they flew to Lebanon.

Viphea remembers his first Halloween, which took place a couple weeks after their arrival.

“My cousin and I thought that this is a great country,” he said with a laugh. “How many country do you know that you go around at night and put on strange makeups and go get candies?”

That was probably one of the easier adjustments for the family to make in their new country.

Photo courtesy of Ken Standle

“I was 18 and I found out language is probably the hardest part,” said Sara Mam, Sarath’s son and Viphea’s cousin. “That’s what we were facing, difficulty with the language from the beginning.”

Kanchana agreed language was the hardest adjustment, but noted that their new American friends set up classes to help them learn. Weather and food were also different.

“We weren’t used to cold weather,” Kanchana said.

Hail was completely foreign. Viphea fondly recalls the first time his grandmother, Kang Mam, saw the strange white pebbles falling from the sky.

“She was inside and she hear this rumbling on the roof and she look outside and she call us in and go, ‘Oh, who would do such a thing? Who throw these rocks all over the yard?’”

Kang thought it was rock salt, which is commonly found in Cambodia, Viphea said. He laughed when telling the story, but remembering his grandmother made his eyes tear up.

The Mams also had to learn about American food.

“Hot dog is funny to us,” Viphea said. “What is hot dog? What do you mean ‘hot dog’? Why would you call (this) after an animal, and why do you make it hot? We don’t understand that the first time.”

Kang was also perplexed by America’s clothing.

“She always thought that America is such a rich, industrial nation, but why do they wear such a small, skimpy clothes when they go out in the sun?” Viphea said.

What’s more, why would they want to go out in the sun with little clothes when it is hot and the skin would get darker? This way of dressing in hot weather was opposite to how Cambodians lived, he said.

As the elder, Kang was entitled to respect from the family.

“The older they are, the more we revere and respect them,” Viphea said.

After her husband had passed away, Kang devoted herself to Buddhist monastery life in Cambodia, and continued to shave her head after arriving in America as part of that practice.

“Younger people, we’re not supposed to touch the head of the elder. It’s a sacred thing. But I do distinctly remember my friends come over from Queen Anne and several friend found her fascinating, and they hug and they would touch her head, and she always thought that was such a funny thing because she never encountered these kind of physical (things),” Viphea said.

The Mam children attended Queen Anne school, later graduating from Lebanon Union High School.

“I don’t remember much except that it’s a nice small town that we came to,” Sara said.

Photo courtesy of Tina Tran

“We were very fortunate, like Vip said, that we came to a small town and then we get to know a lot of wonderful people that we came across in that town, mostly our sponsors.”

In fact, the Mam family tries to make a reunion to Lebanon every year to visit the memorial places of their grandmother and other family members who have since passed.

Viphea recalls Principal Gary Fuller’s trademark pencil behind the ear, and remembers teachers such as Vanda (Scott) Recek, Christine (Reed) Barreto, Doug Axen, Lyle Brown, Ron Easton, and librarian Ashley Leppink.

To this day, he stays in touch with Queen Anne’s former principal, Buzz Collins, who is “like a hero” to the Mam family. He also stays close to Robert and Eilene Ward, and Tom and Winnie Standley, who are “like family” to them.

“Those are the folks at least I would always make concerted effort if I’m in the neighborhood to pay a visit, because they mean a great deal to us,” Viphea said. “We could not thank them enough. We’re forever grateful that they took us in and then give us a start in Lebanon.”

Viphea graduated from Oregon State University and got a job at a lab in California, working as a molecular biologist and learning under Nobel Prize winner Dr. Kary Mullis. Today he is a biotech consultant for startups, helping to evaluate DNA and RNA technologies.

Photo courtesy of Ken Standley

His brother, Achharya (Archie), joined the Marines and fought during the first Gulf War.

Sara was 18 when he arrived in Lebanon. He finished high school and moved on to Linn-Benton Community College, then took a job for the Lebanon Community School District in 1982. Today he works as a teacher’s assistant. Sara has three children and two grandchildren.

Kanchana graduated from the University of Portland. She returned to Cambodia with her husband in 1992 “to help the country rebuild after the violent take-over of our country,” she said.

She helped women learn computer skills, sewing, beauty shop work, and establishing small businesses. Later, among other things, she worked with the Cambodian American National Development Organization and the Sikal organization, where she worked on moral and ethical issues in the country.

Kanchana has two children and two grandchildren, and currently resides in Portland.

Sakal graduated from Oregon State University and works at Intel. She has two children.

Both Sarath and his son Sara have visited Cambodia, and Khon returned there to live.

Kyly family

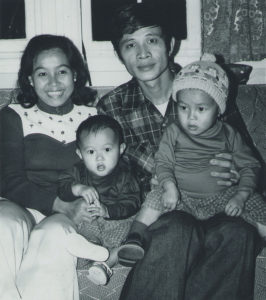

Photo courtesy of DeL’Aurore Kyly

DeL’Aurore Kyly and her brother Luna were toddlers when they arrived in Lebanon.

Their father, Chhrouk Kyly, moved to Laos from Cambodia in 1968, and there met his wife Chat, a Vietnamese who lived in Laos most her life.

“Victor (Chhrouk’s American name) left Cambodia because the communists were killing people,” DeL’Aurore said. “That’s how he ended up in Laos and met my mother. Both of them had to do a lot of different work just to make ends meet. My dad did finally land a good job, working for a packing and transport company in Laos that paid well.”

Chat, now called Susan, taught French in Laos. Since she could also speak a little Thai, the couple decided to sneak into Thailand in 1975 to escape the communists.

“They remembered taking a ferry to Nong Kai, Thailand,” DeL’Aurore said. “My mom disguised herself like a Thai woman selling vegetables. They both hid money in their clothes.”

When they reached the United States, a wave of relief fell on the Kylys, DeL’Aurore said. They finally felt safe.

The family arrived in Lebanon, along with the Mams, in October 1975. Before their arrival, the community had made living arrangements for both families.

Photo courtesy of DeL’Aurore Kyly

“I was looking at some of the old paperwork from the refugee committee and it’s amazing the effort, time and resources they pulled together for our family,” DeL’Aurore said. “I will be forever grateful for the kindness they’ve showed us.”

The Kylys moved into 551 E. Sherman St. The house was outfitted with furniture, clothing, house supplies and food. Marietta Leppink was one of several instrumental people involved in organizing the refugee welcome.

“It was very time-consuming and we gave it our all,” Leppink said.

She recalled meeting Susan Kyly when she picked them up from the airport, and noted Susan was a tiny thing, “no bigger than a minute.”

Susan expected America to only have skyscrapers, so arriving in Lebanon was a bit of a surprise to her when she saw the town only had one and two-story buildings, DeL’Aurore said.

“My mom also remembered seeing the trees, and because there were no leaves, she thought that’s just how trees are in America,” she said. “She forgot that it was autumn and the leaves had already fallen off the trees.”

And for the longest time, they didn’t realize it was safe to drink tap water. In Laos, the water always had to be boiled, so it was “a treat” for Susan to learn she didn’t have to do that anymore.

“She seemed most amazed about the grocery store, how much was available and how orderly it was. She specifically mentioned buying chickens without feathers, which I thought was hilarious,” DeL’Aurore said.

Leppink recalled taking the families to church for their first Christmas in America. They attended Bethlehem Lutheran, and the congregation sang “Angels We Have Heard on High,” wherein the “o” of “gloria” is sustained for a long period of time.

“They started to laugh. And they laughed and laughed. And I thought, you know, we’re so used to that, but it sounds like wailing I guess. Anyway, so they got us to laughing,” she said.

Photo courtesy of DeL’Aurore Kyly

Victor was immediately given a job at Willamette Industries, thanks to John Latimer, where he worked for the next 30 years.

“He appreciated not having to always ‘hustle’ for work,” DeL’Aurore said. “Finding work in Cambodia, and then Laos, was difficult and you always had to look for ways to make money. He didn’t have the same anxiety over money in America like he did in those countries.”

Susan got work as a nanny for a family with three kids. Recently, those kids visited DeL’Aurore and shared with her a story about when their parents, both teachers, found out Susan spanked the kids.

“The mother said, ‘Is that what you do in your country?’ and Susan said ‘yes,’ and they’re like, ‘OK,’” DeL’Aurore said. “It was like, ‘Carry on. Take care of them as that’s how you would normally take care of your kids.’”

The whole Kyly family now resides in Portland. DeL’Aurore has two children and Luna has one. Their father has since visited family in Cambodia.

“My parents are so thankful for all the help they received over the years from the Lebanon community,” DeL’Aurore said. “It was so nice to hear them talk about how the community came together to help us.”

Mao family

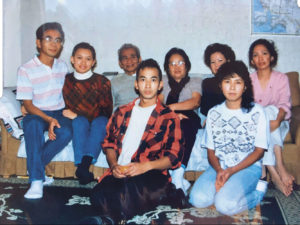

Photo courtesy of Chhiet Mao

Chhay Mao was a military judge in Cambodia when the Khmer Rouge took over the country.

His son, Chhiet, remembered seeing the debris of war scattered throughout the land – downed planes in rice fields, and several anti-aircraft guns placed in front of a school.

The local theater was damaged and buses were blown into pieces after a bomb had landed. Chhiet noticed parts of animals and shoes without owners lying about. He saw the bodies and smelled their flesh as people gathered them together.

In Phnom Penh, the family erected bomb shelters in every corner of their home, since the area was bombed weekly by the Khmer Rouge.

Despite all this, Chhiet, being a child, wasn’t afraid for his life, because this was normal, he said. And his dad underestimated how brutal the insurgents would be during their eventual rule.

“He didn’t think they’re gonna come in and just kill everybody,” Chhiet said. “He think that they only go after the higher ranking official. So they thought he was gonna go to jail, but he did not think that they were coming in and just decided to kill everybody.”

Chhay decided to escape, and took with him his youngest children, Chhiet, 12, and Nouma, 11. They boarded the same plane with Viphea Mam, and flew to Oddar Meanchay, a northern province on the border with Thailand. Then they waited for the rest of the family to meet them there.

“My mom has a high position in community, too, so she can’t come because the older brother and the other one, my sister, had to have exam at school, so they can’t come,” said Nouma Mao.

“I remember when I was a kid, every day I went to the airport and watched plane land, hoping to see my mom come out of the plane. And it never happened,” Chhiet said.

After the Khmer Rouge overtook Phnom Penh, the planes stopped arriving.

Photo courtesy of Chhiet Mao

“That’s when we realized that that’s not going to happen, that we’re not going to see each other again. So that’s when we flee to Thailand,” he said.

When they later landed in the United States, the first impression that stood out to Chhiet was a girl with “white” hair.

“So we call her the white hair girl, which is blonde. We just never seen that,” he said.

The family saw a mall for the first time, tasted sliced white bread for the first time, and experienced their first cold weather. It was all “amazing,” according to Chhiet, and tasting hamburgers for the first time was “interesting.”

“I come during the fall, during the beginning snow, and I seen the snowflakes and I was inside of the car,” Nouma said. “That’s the only thing that alert me the most is the weather. I enjoy the cold weather because it feels good on your skin; on my skin, anyway. And I felt safe inside the car.”

As children, both felt embarrassment for their new situation. Coming from a well-off family in Cambodia with a large house, Chhiet was embarrassed by his apartment in Lebanon and living on food stamps. Nouma was placed in a younger grade at school, which embarrassed her because she was older than everyone else.

As a child, it was easier to absorb the new culture, but their father was traumatized by what he escaped, Chhiet said.

Chhay wrote a series of stories for the local paper, detailing the horrors of what was taking place in his homeland. Then he moved to San Diego to take a job, leaving his children in Lebanon to live with different families from the church.

The Mennonite church in Lebanon had sponsored the Mao family. Chhiet remembered the pastor as very kind, and recalls living with the Brennemans, Wittrigs and Faye Dykast.

“They were all wonderful. There were just amazing people and I had so much fun when I was a kid,” he said.

He remembers learning to shoot BB guns, visiting different places, and basically living the country life, he said.

Nouma worked a paper route and picked strawberries to earn money, she said. One of the reasons she appreciated living in Lebanon was because she could live and sleep without the threat of shotguns and bombs always going off, she said.

“They just want to socialize and think about God and stuff,” she said of her Lebanon friends. “It’s just focus on God and what God have for you.”

Their stay in Lebanon was short-lived, though, because they moved to Portland a few years later when their father got a job there.

Chhay never gave up trying to locate his wife and remaining children who were left behind in Cambodia under the rule of the Khmer Rouge, Chhiet said. He kept writing letters and sending photos until, finally, the missing family members were located in a refugee camp after the insurgents fell.

“I remember the first time I saw her when she came to America, and I just break down crying in front of everybody, and I usually don’t cry, but I remember that clearly,” Chhiet said.

Photo courtesy of Chhiet Mao

His mother, Van Chim, and two of her other children returned to the family in Oregon. Only one of the daughters didn’t make it. They don’t know what happened to her.

After Chhay retired, he returned to Cambodia to help the people left in the wake of a long war.

“He feel like he should help Cambodian people to improve the lifestyle,” Nouma said. “He helping them to get a job, because if they don’t get a job, he think that they would steal for a living, so he said the best way to do it is get a job for them so they don’t have a reason to steal.”

And that’s what he did until his death.

Nouma visited Cambodia once, but noted she didn’t really like it because it made her sad.

She now lives in Beaverton with her mother. Chhiet is an artist, landscaper and filmmaker in Texas.

He became a Christian when he turned 32, and now focuses on taking the gospel of Jesus Christ to the media, he said. He wanted to express gratitude to the sponsoring families in Lebanon, especially since he described himself as an angry rebel during that time.

“I just want to let the people that sponsor us know that when they did that, they plant an amazing seed. I just want to let them know I am so grateful. I am a different person. I didn’t make it easy for everybody that sponsor me, and I know that,” he said.

Surviving under the Khmer Rouge

After the Khmer Rouge fell in 1979, Sara’s older sister, and Viphea’s mother and siblings were located and flown to the United States. Viphea’s mother, Lam Hang, and sister Chhorvy Hoy described life under the Khmer Rouge.

As soon as they entered Phnom Penh, the Khmer Rouge ordered everyone, at gunpoint, to evacuate the city, and told them bombs from America would soon drop, said Viphea, who translated for his mom. A few million people had three days to head into the countryside, no exceptions.

Hang waited until the last minute to leave, hoping to first be reunited with the rest of her family. She didn’t know they had fled two weeks earlier into Thailand. Finally, she gathered what food and belongings she could, and began the trek with her children toward Siem Reap.

Per the custom of the Khmer Rouge, Hang was separated from her children and placed into a work camp. Being the wife of an official, the family was at risk of certain death, so she told them she was the wife of a farmer, and she instructed her kids to say the same.

The oldest sibling was disabled by polio, so she was given the task of taking care of the babies. Chhorvy and her brother were placed with all the other separated children in a group camp.

Chhorvy worked for the insurgents, and she would sometimes walk more than an hour to bring food for her mother and older sister. Fish scraps, rice soup, banana “stuff,” whatever she could salvage, she said.

(Image from wikimedia.commons)

For Hang, it was a hopeless time. She was required to work hard, and the only thing on her mind every single day was to complete the tasks she was given in order to eat and survive.

“It’s come down to the basic level of keeping herself alive, much less to think about her children, because it’s in a great despair. There’s no hope. It’s an endless cycle of work to survive,” Viphea said.

Chhorvy was often tested by the Khmer Rouge, which systematically tried to eliminate all intellectuals.

They suspected her family was from a high position, so they tried trapping her into telling the truth, she said. They used food to tempt the children into talking, and tried to get Chhorvy to demonstrate she was educated.

She said she almost slipped up a couple times, but kept herself alive by working hard and telling them she did not know how to write or do math.

Meanwhile, Sara’s sister, who stayed in Cambodia, was questioned as well. She could not work like a farmer, and told them about her husband’s education. She disappeared for six months, and Hang figured she would never see her niece again, but she did return and explained she had worked in the kitchen for the Khmer Rouge.

A year or two into their rule, the killing by the Khmer Rouge increased.

Chhorvy was with her mom when one of her uncles stopped to say goodbye. He was going to flee to Thailand to escape the killing, she said. Soon after he left, shirtless horse riders with swords came through, dragging people behind them.

After that, Chhorvy and Hang joined others to look for their missing relatives, and they came upon a temple that was covered with blood, she said. Among the bodies found was an unrecognizable body that they believe was her uncle.

“They slit his throat, and blood everywhere,” Viphea said. “They hardly recognize the horror scene of bodies, mangles, decapitations.”

In 1978, the shirtless riders came to their camp again and killed many people in front of them, Chhorvy said. Later that year, she saw an airplane fly overhead at night and saw men dressed in tiger clothing looking at the camps.

“I told my mom,” she said. “My mom say ‘don’t say nothing.’ Whatever I see or saw, don’t say, no tell nobody. Just keep secret.”

Photo courtesy of Viphea Mam

A couple months later, Vietnamese tanks overtook the camps, she said. Nobody understood what was happening, but Hang used the chance to grab her children and escape. They walked for about a week, passing bodies all along the way, until they reached Hang’s birth place in Siem Reap.

“We stay under the mango tree, and then my mom had to go looking for the food, for the rice,” Chhorvy said. “She just left us there and then she gonna go looking for the relative, too, on my dad side.”

By late 1979, the rule of the Khmer Rouge had ended, but Hang was still just trying to survive, Viphea said. Meanwhile, the family in Lebanon began writing letters, seeking information on their lost relatives, and were rewarded with the news when they had been found.

“She feel tremendous happiness knowing that families, two sons, husband, brothers, relatives is alive and able to sponsor her over,” Viphea said. “She feel much gratefulness for the opportunity to able to survive, first of all, and then ultimately reunite and resettle.”

Political Turmoil in Modern America

Today, Chhiet said, he questions how close America is to falling into a similar history as Cambodia.

“Our country is really in trouble right now, and we are so close to self destruct,” he said of America.

When he was a child, Cambodia was a beautiful and peaceful country, but he saw it change in the short span of five years, with slaughter that killed a fourth of the nation, he said.

“It happened so fast, and what I’m so concerned about that, the sign that I went through all that, I’m actually seeing it here in America,” he said. “It starts out with two leaders who did not like each other, and they divided the country. That’s how Cambodia got started. It’s basically one guy decided that he didn’t like what the other guy was doing, and he divided the country, and it just escalate and escalate until there’s a tipping point.”

Chhiet said it was a communist faction against the newly independent government of Cambodia, and the tipping point was when President Richard Nixon disregarded the Geneva Convention and bombed Cambodia in an attempt to win the Vietnam War.

He calls the United States “the last frontier,” a place he loves, a nation consisting of many good people, but also a nation where one party is not afraid to take their fight to the next level, and another party willing to match that.

(Creative commons license, joanbrown51)

“We’re in a situation where, like in Cambodia, like when they have protests, I remember it started out just a protest against another party. Then it escalate where one party is not afraid to go and shoot another party down on the street, which is actually what’s happening right now (in America),” he said. “So that’s the next level of escalation.”

But he hopes it doesn’t get any worse, he said. He expects to see small factions break into war against other factions, but hopes it never escalates into a civil war like that in Cambodia.

As a Christian, Chhiet said he stands on the belief that he is called to be bold and have courage, and to not choose a political party.

“For me, it’s what am I willing to do to save our country? And that’s the bottom line. What are you willing to do to save your country?”

“I struggle with my own sin, but I do understand (God’s) grace. I understand that he loves and I have to project that to everybody I come into contact with, grace and love. Which is really hard, because I came from a very ugly world and now I’m supposed to love, to be kind, to be gentle, to be meek.”