After her own experience behind bars,

Nancy Pance has plans to help other ex-inmates

By Sarah Brown

Lebanon Local

Eleven years ago, Nancy Pance walked out of Coffee Creek Correctional Facility with $250, a flip phone, and the gray sweat suit she was wearing.

She had just spent three years of a six-year sentence for second-degree robbery and coercion, and a couple of drug possession charges.

Today she runs a successful enterprise at Anytime Fitness in Lebanon and is about to open a new business called Opportunity Oregon, a recruitment agency for ex-convicts like herself who need a job to successfully integrate back into society.

When Pance got out of prison on conditional release, her brother picked her up and took her to a halfway house in Bend. There, Pance was required to attend meetings, complete classes and find a job or enroll in school; otherwise, she would have to return to prison to complete her sentence.

“It’s kind of scary when you’re in an institution, and then suddenly you’re free,” Pance said. “You’re on your own and you’ve got to do all these things.”

Pance walked eight miles every day to the bus station to look for work, she said. An employment agency helped her put together a work resume, but it didn’t look very good because her work history from years prior was spotty, and the most recent work experience happened while she was in prison.

“I was ready to take a job anywhere because I was kind of nervous because I had three years of a prison sentence hanging over my head if I didn’t get this job,” she said.

At that time, in 2010, application forms from employers often included a checkbox for applicants to indicate whether they had a conviction record. It wasn’t until 2016 that a new Oregon law required those inquiries to be banned until an initial interview or conditional offer of employment was made.

So for Pance, all her applications indicated she had committed a felony, and she was required to explain it was a gas station robbery.

Everybody told her “no.”

“Nobody would give me a chance,” she said. “I’m like, ‘I’ll take a job anywhere; just let me work.’ And I’m starting to get stressed out. I’m thinking I’m gonna go back (to prison) because I can’t find work.”

The turning point for Pance followed an interview at a fast food chain.

It was a hot June day and Pance had been walking all over town in search of a job, she said. The manager at a restaurant came out and asked what she got in trouble for. And as always, Pance was turned away.

“She literally told me that I was a liability and she couldn’t hire me,” Pance said. “I was so sad when I left there. I might have been cussing and swearing. I was so pissed and I was so sad. I’m like, ‘Nobody’s giving me a chance. This is the most awful feeling. I’m getting out and I’m trying to do the right thing. I’m going to all these classes, and I’m gonna go back (to prison) if I don’t get a job. This is so scary for me and this just isn’t fair.’”

She understood that employers would rather hire someone without a robbery conviction, she said, but Pance was on the right track in her life and wasn’t catching a break. So she had only one recourse: go to school.

“I said, ‘That’s it. I’m going to go to school, and I’m gonna get my business degree, and someday I’m gonna help people like me that feel this way right now.’”

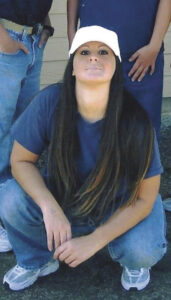

Courtesy of Nancy Pance

Eleven years later, her dream has become reality.

Pance was born and raised in Southern California. She had a good family, but admits she was just “one of those kids” who acted up and made wrong choices.

She would run away from home, had been kicked out of a couple different schools, and spent time in juvenile hall.

Her parents, at a loss for what to do, sent 14-year-old Pance to a church foster program in Bend that helped wayward children.

“I was still fighting my own little demons inside, and feeling uncomfortable being at that age and living in other peoples’ homes,” she said. “So I turned to drugs.”

She was 15 when she had her first of three children. As a single mother, Pance would use drugs to keep herself awake while working two or three jobs. Though she would get clean from time to time, she always found reasons to return to old patterns, she said.

It got so bad at one point that she literally knocked on doors looking for treatment, she said, but was denied because she wasn’t in any trouble that qualified her, nor did she have thousands of dollars to enroll in a program.

Her drug use accelerated between 2002 and 2007, she said.

“I was in my 20s. It got really bad, and I just spiraled completely out of control,” Pance said. “Nobody wanted anything to do with me.”

Her brother wouldn’t let her into his home because she was so strung out and messed up, she said. Her weight was close to 100 pounds and she was living out of a backpack. Her dad paid her a visit in 2007, and left brokenhearted.

“He went home and wept, and he prayed for God to spiritually arrest me,” she said.

A couple months later, Pance was, literally, arrested.

Her boyfriend was at a rehabilitation facility in Minnesota at the time, and Pance was desperate to get there. They had both been to the program before, but had relapsed, and he had checked in to get clean again.

Pance didn’t have the money to go, but was trying.

When she stopped at a friend’s house, Pance met two men who were talking about committing a crime that would yield fast cash.

“Something inside of me said, ‘You can get to Minnesota. You can go get yourself cleaned up. You can go get the help that you need. It’s there waiting for you. This is your plane ticket.’ And I didn’t care,” Pance said.

“I had already lost everything. I’m like, ‘What do I have to lose?’ I was in a state of mind with all the drugs and the clouding and just not caring, that it didn’t matter. I’d do whatever it took, you know?”

Very early the next morning, Pance and the two men drove to a gas station. She acted as a distraction and lookout while one of the men robbed the cashier. Then they left.

It wasn’t long before her name was released to the police as one of the suspects. Blockades and barriers were put up around town, and Pance was “strung out” and scared.

She went out to a boulder on the side of the road, got on her knees, and wept.

“Part of my message is my faith, because despite everything that was happening, and no matter how cloudy my head was, where my life had gone, even though I had lost everything, I still had God,” she said. “I said, ‘Lord, please save me. I don’t know what to do. I need your help right now more than ever. I’ll do whatever you want me to do. I’m done with this.’”

Recalling the moment 14 years later in a conversation, Pance weeps.

“I literally wept and I reached up. I said, ‘Jesus save me because I can’t save myself. I can’t stop,’” she said. “And suddenly, despite all the drugs, despite everything that happened (and) the madness in my head, I had clarity. I knew exactly what I needed to do.”

Courtesy of Nancy Pance

Pance turned herself in and owned up to her part in the crime. Her attorney, who to this day is now a good friend and mentor, told her that she could get the help she needed to change her life while in prison.

“I remember when I first got to the jail, everything sunk in,” she said. “My emotions were so up and down, but I remember looking at my arms, looking at my body. I was tiny, shriveled, gone, almost dead. And I just said I was relieved. It’s over. It’s over.”

While being processed for her conviction, Pance’s boyfriend – the love of her life, she said – died from an overdose. She cried for three days, and she said his death was her “spiritual awakening” to stay clean.

In prison, Pance used humor to deflect stress and problems with the “mean girls,” she said. She worked jobs in the canteen warehouse and coffee cart, and took advantage of multiple programs offered.

She realized it was her opportunity to learn new skills, build herself up, and change her life, she said. One of the programs she joined – called Lift at the time, but now called Hope – was a cognitive thinking repair class. It was the most difficult experience of her life, but the most life changing.

Now, Pance returns to that class in prison to speak to other girls about her experience. She tells them she knows exactly what they’re going through, but if she can come out on the winning side, so can they.

“That’s where I started realizing I need to do more of this. I need to help the other inmates. I need to show them that it’s OK to hit the very bottom and lose everything,” she said.

Courtesy of Nancy Pance

Pance was once in their shoes, she tells them. She wore those jeans, those shirts, those lanyard ID tags. She didn’t know what was going to happen, and she had nothing when she got out.

“Now I have two businesses, a side job, and family that loves and supports me – family that didn’t want to talk to me (at one point) because it was so bad.”

Inmates’ responsibility is to use their time in prison to change behaviors so they can be ready for life on the outside, she said. In fact, to help encourage prisoners, Pance has started writing a book about her experience and how inmates can change their patterns for better.

In 2013, Pance received her degree in business administration with specializations in accounting at Central Oregon Community College, and got her first job in sales at a cell phone company. She worked her way to the top in a couple of years, but kept her eyes on the ultimate goal: to own her own business.

“I started saving, and I didn’t know how I was going to start my own business, but I knew it was gonna happen,” she said. “I just believed. I’m like, ‘If I just keep working really hard and be grateful for what I have, it’s going to work out.’”

And it did. Her brother, Joseph Carmack, told her about the opportunity to buy Anytime Fitness in Lebanon, and they were handed the keys in 2015. They turned it around, going from 120 members to almost 600 in five years.

Today, Carmack is her business partner at both Anytime Fitness and Opportunity Oregon.

“I owe so much credit to my brother and my business partner,” Pance said. “My brother is my total mentor. He is the one that I call for everything. When I was down and in my hardest moments, I’ve called him and he’s just been right there for me in every way, and he’s always believed in me.”

Since moving to Lebanon for the business, Pance surrounded herself with new friends, and now volunteers for the Strawberry Festival and Lebanon Chamber Ambassadors. But in order to be able to invest herself fully into Opportunity Oregon and related outreach programs, Pance made the hard decision to put Anytime Fitness up for sale.

Opportunity Oregon, which is located in Springfield, is a recruitment agency that will pair recently released job seekers with employers who are willing to give them a chance. It is expected to launch by the end of March.

More than 70 million Americans, or one in every three persons, have a criminal record, and at least 27 percent of them are unemployed. Unemployed parolees are revoked at a rate of 500 percent higher than those who are employed, and about 50 percent will return to their former way of life because they can’t obtain work.

Courtesy of Nancy Pance

Through Opportunity Oregon, Pance screens her clients thoroughly and selects only the top 10 percent of current inmates who prove they are changing their behaviors while in prison.

“I want to see what type of inmate they are in there to make sure that they’re the ones that are actually making those changes in their life,” she said. “Those are the ones that I want to help place, because if they’re showing that pattern and behavior change in there, then that’s my prime choice.”

Finding those “prime” inmates is harder than finding employers who are willing to hire them, she said.

“When it comes to the employer clients, I can’t tell you how many people are ready to actually jump aboard,” Pance said.

Part of the eagerness to hire former convicts is the benefits they receive by doing so, she said. Employers are entitled to a $2,400 Work Opportunity Tax Credit for hiring an ex-felon who’s been released within the past year.

There’s also a federal bonding program for up to $5,000 insurance, but Pance said statistics prove formerly incarcerated people who obtain work do not reoffend.

Carmack agreed, noting it’s not some sort of charity case to hire an ex-convict, but, rather, a good business decision.

“National studies show that the quality of work and the longevity of employment is greater than if you’re just going to hire somebody off the street who doesn’t have a criminal record,” Carmack said. “It seems counter-intuitive, but it’s true.”

And he knows that Pance is in the perfect position to connect former inmates to employers.

“Having been through the same trials herself, she has a unique vantage point and empathy that aligns with what we’re trying to accomplish with Opportunity Oregon,” Carmack said. “Our unique relationship with the Oregon Department of Corrections, and knowing what we’re looking for, gives us the ability to pair the right people for that kind of work.”

Looking back over her life, Carmack is grateful to have his sister back, he said.

Courtesy of Nancy Pance

“From the very earliest age, she’s been absolutely chock full of energy and enthusiasm, (with a) nothing-held-back, heart-on-the-sleeve kind of personality,” he said. “This little girl who was so full of love pretty much disappeared, replaced by someone who we all figured was headed to, honestly, a very early grave.”

But with help from the Department of Corrections, Pance came out of prison a completely different person than how she went in, Carmack said.

Since her release from prison, Pance had been selective about who she shared her story with. She knew that one day she would share it with the rest of the world, and felt today was the right time, “according to God’s timing,” she said.

She wanted people to first know her for who she really is before hearing about who she was for a period of time.

“It’s hard not to love Nancy,” Carmack said. “She has this genuine enthusiasm for life and authentic love of those around her that just draws people in.”