By Sarah Brown

Lebanon Local

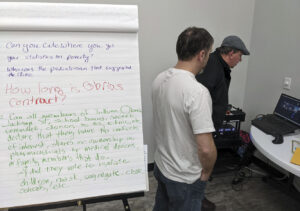

Following an uproar during the public comments period at the Jan. 13 school board meeting, parents and concerned citizens of the Lebanon Community School District held a town hall meeting Feb. 8 to discuss the school-based health center announced at the Dec. 9 board meeting.

The LCSD hosted an online forum (viewable at youtu.be/4_TdLoro1YI) at the same time, which included Supt. Bo Yates; Rachel Cannon, the district’s interconnected systems framework coordinator; Marty Cahill, CEO of Samaritan Lebanon Community Hospital; pediatrician Dr. Dana Kosmala; Debbie Tracy, CEO of Obria Medical Clinics, a local community care clinic that focuses on women’s health; and others, to explain how a school-based health center can benefit students.

School-based health centers

A school-based health center is a medical clinic located at a school or on school property to provide basic health services for students. They are required to provide services to all students regardless of their ability to pay.

Offered services include such things as routine physicals and exams, treatment of illnesses and minor injuries, immunizations, substance abuse counseling, mental health counseling, health classroom education, medication prescription, and reproductive services.

Cannon’s PowerPoint presentation noted that abortion procedures or referrals, and hormone replacement therapy, which parents have voiced as concerns, are not included. Cannon also mentioned they are “really hopeful” that they might be able to include dental services at the clinic.

“A school-based health center is about leveling the playing field so that our most vulnerable students can engage in successfully in learning,” Cannon said. “(It) reduces barriers such as costs, transportation and concerns about confidentiality that prevent students from seeking the services they need.”

For those with health insurance, transportation and knowledge of the system, it’s still difficult and expensive to access, Cannon said. Thus, it’s even less accessible to those lacking insurance, transportation or an established provider.

School-based health centers (SBHC) were established in the U.S. in the 1960s, and in Oregon since 1986. There are currently 78 SBHCs in the state, with none in Linn County. The proposed Lebanon SBHC would be funded by the School Health Services Planning Grant in two phases through the Oregon Health Authority. Part of the grant is funded in Phase 1 for the district’s committee to assess needs, and to plan. Phase 2 provides funding for implementation of the SBHC.

“School-based health centers are not open to the public, and they are only for our students,” Cannon said.

Though the proposed clinic is expected to be at the high school, its services would not be limited to only its students; district students of any age will have access to the services.

However, though the district cites “access” as an SBHC benefit, Asst. Supt. Jennifer Meckley said students from the elementary and middle schools will have to find transportation to the high school in order to access the clinic.

On the upside of this discrepancy, it will be easier to establish care and schedule timely appointments with this center as opposed to a regular medical provider, she said.

When someone at the forum asked if home-schooled children could access this SBHC, Meckley responded that current plans are for only LCSD-enrolled students.

Timeline

The idea to establish a SBHC in Lebanon came up in October 2021, six months after an advisory committee was formed to determine how different service agencies in Linn County could partner to assist students.

In August 2020, the Linn Benton Lincoln Education Service District, which provides educational programs and services, suggested that the LCSD form an Interconnected Systems Framework (ISF), a network of community agencies (such as medical, mental, youth and faith organizations) that work together to support students.

The district was not ready to form an ISF until January 2021, Meckley said. The first meeting of the Mental Health and Wellness Program advisory committee was held in April of that year. The committee included representatives from Samaritan Health Services, Linn County Alcohol and Drug Prevention Specialists, Linn County Juvenile Department, Linn County Mental Health, Trillium Family Services, Greater Santiam Boys and Girls Club, Jackson Street Youth Services, Linn Benton Lincoln ESD, Western University of Health Sciences, a community faith-based organization, and LCSD staff, including Supt. Yates, Meckley, other administrators, mental health specialists, a school nurse and social workers.

“We do not have all the answers, but we know working together we can be more focused and effective in supporting students in need,” Yates said at the forum.

Though the ISF’s goal started with a mental health focus, data from the discussions made the team realize there were more needs than just mental health, Meckley said.

The committee, divided into four sub-groups, met twice a month. In October an unnamed pediatrician suggested a SBHC, and the idea was introduced to “district leadership.” Research took place in November, and the proposal was presented to the school board the following month.

Until then, the school board knew nothing about this.

That annoyed former board member Todd Gestrin, who stepped down from his seat last November. He said that although it’s not efficient for the superintendent to inform the board on every action he takes, certain situations would best be served by communicating them to the board early on.

The SBHC would be one of those issues because people would have strong feelings about it, Gestrin said. The superintendent had opportunities at every board meeting since the beginning of January 2021 to simply tell the board what was coming.

“So you don’t just surprise everyone, and especially the school board,” he said. “The school district belongs to the public. It doesn’t belong to Bo. It’s a matter that needs to be open for honest conversation. But when the school board appears that we did something behind the public’s back, there is no trust and it all falls apart.”

Gestrin added that he believes Supt. Yates does a lot of things well, but communication is not his strong suit.

Board Chair Mike Martin agreed that seven months of advisory committee meetings “is a long time without in-depth interviews, surveys or focus group discussions with board or community.”

He tallied 56 meetings between the sub-groups of the committee missed by the board and community, both of whom should have been included from the beginning, he said.

Martin and board member Richard Borden attended the town hall meeting and forum, and made themselves available to attendees.

During a question-and-answer period, Supt. Yates was asked if he would move forward with the SBHC if the school board does not approve.

“I think we’ll have the support of the school board moving forward,” he replied. “There’s both my leadership team, the school board, and we want community support as well. I would be very surprised if we weren’t supported.”

Borden’s response to Yates’ answer was that no one on the board has discussed the issue with each other or with Yates.

“I don’t know how he knows how I feel,” Borden said.

Following the forum, people at the town hall remained in attendance to hash out their thoughts.

Borden told the group that he does not support the SBHC.

Martin has done his own research by visiting two SBHCs in the state and the East Linn Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) in Lebanon, which charges patients based on ability to pay.

“In my opinion, we need to take the time to have some meaningful communications and conversations with the community,” he said. “Seek the community’s input on shaping the foundation of what could be a good thing for our students.”

Board member Tammy Schilling said the concept is exciting, but the details need bearing out first.

“Hopefully, we can understand those important details as they relate to our primary stakeholders, Lebanon students,” she said. “I always welcome contrary opinions, too, because I may want to change my mind based on the information that has been added to the conversation.”

Board member Tom Oliver could not be reached for comment.

Community response

When the Lebanon Local broke the story about the possibility of an SBHC at Lebanon High School, some parents began raising concerns, including: whether COVID-19 vaccinations would be given to children of parents who don’t want their family to take the vaccine; access to abortion services; a belief that this proposal centers around making money rather than caring for kids; children being encouraged to access gender hormone therapies; the notion that it is not the school or government’s place to be involved in a child’s medical care; how the services will be paid for, and whether parents will find surprise bills in the mail; confidentiality; funding through the Centers for Disease Control that may promote abortion and gender hormone therapies; adverse reactions a child may have to medication whose prescription was unknown to a parent; and children receiving medical care without a parent’s knowledge.

Oregon law allows minors 15 years of age or older to give consent to medical or dental treatment without parental consent. Minors 14 years or older may access mental health and drug or alcohol treatment without it, with some exceptions. Minors of any age may access birth control services and STD treatment without parental consent.

Parents have access to a child’s MyChart, a web portal providing access to medical records, until the child turns 13, at which point the parent needs the child’s consent to access the records, Kosmala said.

“Our goal is not to keep the parents from the healthcare of their kids,” she said. “We’re going to encourage every child to let the parents know that they came to the clinic.”

Lindsay Pehrson, a nurse and vocal opponent of the proposal, said the consent laws are a huge concern.

“We are talking about children,” she posted on social media. “These children that are easily influenced, vulnerable to peer opinion, just trying to get through their finals and not embarrassing themselves in front of their high school crush. These children are not fully mature at the age of 15. Yet they have the ability to consent for themselves for medical treatments. But they are to (sic) young to drive cars on their own, to be employed, to enlist in the military or vote.”

She added that familial and personal medical histories carry a lot of weight in helping doctors determine the safest treatment options, and a child may not remember those histories or even the allergies to which they’ve reacted.

“These have true consequences for children making their own decisions,” Pehrson said.

Case in point: A Lebanon resident who asked to remain anonymous said her family has a history of medical conditions that require family members to be particularly careful. But based on what this woman’s heard from her grandchildren, there’s a lot of pressure on students to be vaccinated.

As such, one of her grandchildren went to get vaccinated in order to stop being quarantined, to maintain their grades and stop feeling pressured. They didn’t tell anyone in the family about it because they knew there would be a concern, but they felt healthy enough to handle it. The reaction to the shot was, however, life-threatening, the grandmother said.

Our source cried when recounting what happened.

“Nobody knew our family history at all, and they just willingly stuck (the needle) in their arm,” the source said. “If the parents don’t know (what services their child is receiving), we can’t protect our children.”

Waterloo resident Corbin Tolen said he was concerned that taxpayer money would fund a facility just so that it could be handed to Samaritan for free in order for them to operate their practice.

“Not everybody agrees with Samaritan providers,” Tolen said. “Not every parent wants to go and see a Samaritan provider and follow the guidelines of what Samaritan offers.”

A massage therapist, Tolen said he’s seen clients who are prescribed as many as a dozen medications, most of which come from Samaritan.

“If you’re going to the doctor and they’re there to advocate for your health, but their tool in the toolbox is pharmaceutical drugs instead of exercise, health – body work, you know, that’s the real answer to a healthy progression with your life,” he said.

Though Tolen wasn’t a parent, he took issue with the SBHC because kids are the future, he said. Any compromise on a child is a compromise for society.

“The school is not the place for this, period,” he said.

District Communications Director Susanne Stefani, in rebuttal to any “stay in your lane” premise, said the district wouldn’t have the Welcome Center serving hundreds of families every month if it were to focus solely on reading from a textbook.

The needs of students are different now, she said.

Support for the clinic

Lebanon parent Tammy Soper said she had to travel to Albany for her child to receive reduced-fee vaccines – those required to attend school – through the health department, and added that the “extremely high homeless population” in Lebanon may be deterred from accessing free or affordable healthcare if it’s not within reach.

“I am a firm believer in easy access to healthcare,” Soper said. “To add roadblocks to medical access is costly and dangerous, in my opinion. Again, I believe that easy access to medical care is important to the community as a whole.”

Jodie Taylor, a nurse, also cited access to good health care as an important community element. She, herself, she said, grew up poor and received most, if not all, of her healthcare through school screenings.

Chris Maurer, a father to five children in the district, said he has open and honest communication with his children, and he’d be comfortable with them seeking health options if they weren’t available elsewhere.

“I would rather my children regardless of age go get help with an STD or get birth control behind my back than not getting help at all,” he said. “If you are a parent who has a concern about it, I think that your children would probably have an issue with it as well, and you would communicate that with them and you would make it not an option for your family.”

Former Boys & Girls Club of the Greater Santiam executive director Kris Latimer, who has participated in the advisory committee, expressed excitement for the opportunity.

“It’s long overdue, she said. “We’re a low-income community, and so many kids go without the care they need because we have so many kids whose parents are so busy doing so many other things, just trying to keep the lights on and keep their family safe and fed and everything, and sometimes healthcare can slip through the cracks.”

In rebuttal to the transportation question, Pehrson said that as a single mom of two children, she did find a way to get her children to appointments, even when it was difficult at times.

Opponents also pointed out there is already access to free or reduced-cost healthcare at Obria, located at 136 W. Vine St., and East Linn County Health Services, at 1600 S. Main St. and 100 Mullins Drive.

Why an SBHC now?

Why an SBHC now?

Data gathered from the committee’s agencies was presented to support an SBHC. Cannon reported that, according to Samaritan’s 2021 Well Child Check (WCC), 90% of Lebanon students 12 to 18 years old did not get a WCC. Regular WCCs are meant, generally, to ensure up-to-date immunizations and to assess a child’s development.

Other reported data: Prior to COVID, an average of 50 Lebanon high school students accessed the health room daily; 1 in 10 junior students attempted suicide in 2019, and the number of referrals for mental health services “dramatically increased” during the coronavirus; the district’s poverty rate is at 81%; and 135 students are currently homeless.

A 2021 student survey indicated that approximately 20% of the high school’s population felt its emotional or mental health needs were not being met; have gone to the emergency room during school hours; or felt sad, overwhelmed, anxious or angry.

Citing Maslow’s Heirarchy of Needs – psychologist Abraham Maslow’s 1943 paper that ranks human needs, pyramid-style, from universal basic physiological needs such as food to acquired and emotional needs such as self-actualization – Stefani said that a child’s sense of security and belonging cannot be met if the most basic needs of safety and health are not first met.

Cannon pointed out that it’s harder for a child to focus on schoolwork while suffering from a toothache or not feeling well. The SBHC’s goals include improved educational outcomes, care for all students regardless of cost, and freeing up parents’ time from missed work due to medical appointments.

Kosmala said she sees many needs from her clinic’s patients, and she wishes she could have helped earlier. Sometimes parents couldn’t bring their children for help due to work schedules. With a SBHC, however, that child could have been seen the day before.

“I think all these different agencies working together is just to promote a healthier community and healthier kids,” she said.

Cannon said she is scheduled to meet with Oregon Health Authority in March to discuss next steps for the grant that will fund the establishment of the SBHC.