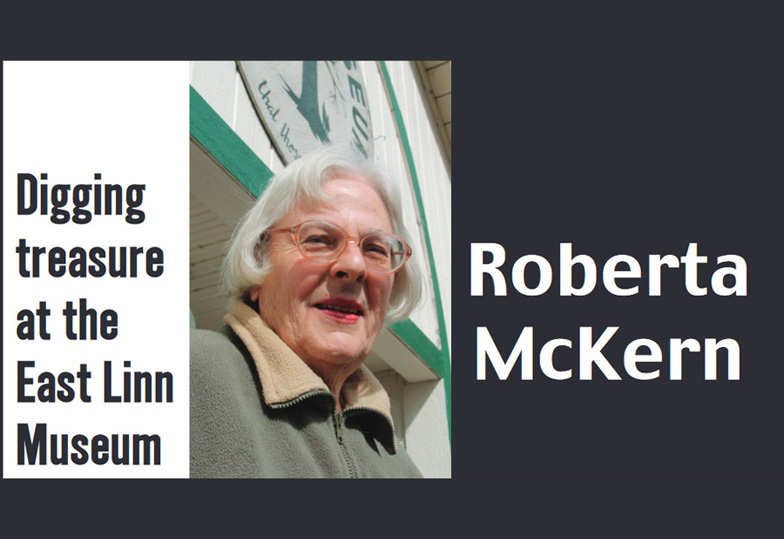

By Roberta McKern

For The New Era/Lebanon Local

Recently, we explored Clifford Merrill Drury’s “Henry Harmon Spalding: Pioneer of Old Oregon” (1936), a new arrival at the East Linn Museum. The book recounts the title figure’s life and experiences as a missionary among the Nez Perce Indians from 1836 to 1846.

As we learned in our early lessons on state history, Spalding and his wife, Eliza, came to Oregon with Dr. Marcus Whitman and his wife, Narcissa. While the Spaldings founded a mission at Lapwai, near present-day Lewiston, Idaho, their traveling companions continued on, establishing a mission at Waiilatpu, west of Walla Walla, Washington, among the Cayuse Indians. When the latter mission was attacked on Nov. 29, 1847, the histories of both came to an end. The Whitmans and others perished in what soon became known as the Whitman massacre.

“Spalding’s” author eased past the horror with a description of the occurrence as it affected Spalding, his wife and their children — particularly their oldest daughter, also named Eliza, who had arrived at the Whitman mission shortly before the event to attend school. Since she spoke Nez Perce, she became an interpreter when a ransom was arranged for women and children spared by the Cayuse.

Drury would focus more on the massacre in a second volume, 1937’s “Marcus Whitman M.D.: Pioneer and Martyr.” Having secured a copy of our own, we’ll give it more consideration as well.

But first we’ll look at two photographs of the victims’ graves, which in their way underscore the growth of a legend around the doctor, sometimes called the “Savior of Oregon.”

Had he not met an abrupt end, Marcus Whitman’s legend as a bold, enterprising adventurer, the first to lead a wagon train to the Columbia River, may not have become so highly colored. However, he wasn’t around to refute hyperbole.

That’s not to say he was less than an intelligent, enterprising, altruistic and compassionate individual. But martyrdom gave him a luster that Spalding, for instance, lacked.

Besides, he had an institution named in his honor: Walla Walla’s Whitman College, where numerous letters, reminiscences and memorabilia provided a wealth of information for Drury to tap for his “Spalding” follow-up.

So, what do the photographs of these graves look like? The first shows an excavated area with earth piled high in its center, its surrounding landscape desolate and bleak. A line of trees marks the Walla Walla River in the distance. The mound does not reach the excavation’s squared edges.

The photograph was taken in 1858, about 11 years after the massacre. The grave holds the remains of 14 people. But the mound is in a second state. Following the massacre, a shallow grave was prepared for the bodies of those killed.

Former Hudson’s Bay Company employee Joe Stanfield was spared. When other men at the mission were targeted, he became the grave digger. Father Jean Baptiste Brouillet, a Catholic priest, came upon his labor and helped him bury the bodies.

However, wolves soon dug into the shallow grave. Something ate part of Narcissa Whitman’s leg. She was the only woman killed. More earth was heaped on the grave.

When soldiers came upon the grave during the 1847-55 Cayuse War, they discovered it had again been disturbed.

Of the scattered bones, Perrin Whitman, Dr. Whitman’s nephew, recognized the older man’s skull thanks to a gold tooth. He’d witnessed his uncle getting the tooth filled by a dentist in St. Louis, when he was brought west in 1843, at age 13.

A wagon box made a casket. The bones were buried once more, perhaps not to be disturbed until 1897, 50 years after the massacre, when Whitman College and others decided to build a more fitting monument honoring its trailblazing, martyred namesake.

What appears to be a cement vault was topped by a marble slab engraved with the names of all 14 dead. Commemorators also set a statue of Whitman on a nearby hill.

Drury could find likenesses of neither Marcus nor his wife, but Perrin was considered a close match. (As an interpreter and otherwise, Perrin had also been involved with the Indian tribes along the upper Columbia River.) So his features were used on the book cover.

A macabre note: Narcissa Whitman’s long, golden locks were visible when soldiers set the scattered remains in the wagon bed coffin. Some removed hair fragments as souvenirs to take back to the Willamette Valley in remembrance. (People saved hair for such purposes in the 1800s.)

So, what about the reason for these graves? Was there something about the year 1847 that triggered the massacre?

Maybe “triggered” is too harsh a word. The situation had been brewing for some time.

In retrospect, some had decided that both the Whitmans had the wrong temperament for missionaries. Narcissa, in particular, has been called haughty and proud. She’d been a teacher for several years before her 1836 marriage allowed her to answer the dream of becoming a missionary. She may have viewed the world through a schoolmarm’s eyes, although she longed for spectacles as she grew older.

A particularly talented singer, she was accustomed to respect. Plus, she wrote of her dislike of having six or seven Indian men in her kitchen while she was cooking.

The Cayuse, too, have been described as proud and haughty — and too much of both traits likely made for a poor mix.

Not only was Dr. Whitman on constant call as a medical doctor, but he also had to be a farmer, stockman, builder and teacher. Like Spalding, he taught by example, growing a garden and crops and encouraging the Indians to do the same, along with raising sheep, hogs and cattle. (The missionaries had built up cattle herds from their initial 1836 stock. Although other animals could be purchased from Hudson’s Bay, the company did not sell cattle.)

The Cayuse were already known as good horsemen. The winter of 1846-47 had been especially harsh, however, and livestock left to winter in the open died in droves.

Whitman and the Indians also planned to sell produce and stock to passing emigrants who had depleted stores, but a new route straight to The Dalles bypassed the mission. However, this didn’t mean the trail no longer cut through the Cayuse hunting range.

Whitman had guided the emigrant train past the mission, blazing the trail. But, according to Drury, Stickus, a Cayuse chief and friend, had done much of the guiding through the Blue Mountains because word had come that the Spaldings were sick at Lapwai with scarlet fever and Whitman went to care for them.

Which leads us to a very real problem at the mission in 1847. That year, emigrants brought measles and dysentery, like scarlet fever, a white man’s disease.

Plus, not all of them continued to The Dalles. Many stayed behind. Some lived in the mission house and others in “The Mansion,” an L-shaped building with a school room and an upstairs.

Each room of these buildings was occupied. For instance, millwright Josiah Osborn (who Whitman had hired to improve his flour mill), his wife, Margret, and their four children lived in the school room. When it came to families, one room had to suffice.

In addition to that year’s emigrants, the Whitmans watched over orphaned children, like the seven Sagers, whose parents, Henry and Naomi, died on the Oregon Trail in 1844; and some half-breed children, among them the daughters of Joe Meek and Jim Bridger, each of whom wanted them to attend school; and those he’d hired to make home improvements.

There were 74 people in all, according to Drury. Many were ill, including Margret Osborn and a young daughter, Salvi. The night before the massacre, it was thought that Bridger’s Mary Ann would die. (She didn’t that night, but soon would.)

Salvi Osborn, however, did die. And when that happened, Narcissa Whitman sought permission to show the child’s body to an Indian, hoping to make it evident that other children, not just the Indians, were losing their lives. Apparently, the Indian laughed at the sight.

The Whitmans may or may not have known of a rumor among the Cayuse that they and Spalding were working together to poison the Indians and take their land.

There were other stories, too, spread by some half-breed men hanging around the mission — Joe Lewis, in particular. Lewis, who’d been born in Canada and attended school in Maine, embroidered upon a conspiracy theory by claiming to have overheard the two missionaries and Narcissa Whitman talking in another room.

Allegedly, the doctor and Spalding spoke of poisoning slowly, while Narcissa said it should be done all at once and ended.

These lies, Drury pointed out, reflected the tale of Dr. Whitman’s watermelons, which were indeed tainted to discourage the Indians from stealing them. This seemed like a joke to the perpetrator, who was not Dr. Whitman.

In the meantime, the Whitmans were considering giving up the mission. The doctor would have preferred that someone relieve him so he could keep up with medical demands. He nagged the missionary board about sending pious people to settle around the mission.

Its head, Dr. David Green, believed that that should be left to providence and did nothing but remind Whitman that he shouldn’t spend so much time on the emigrants, selling them provisions.

Drury said the mission’s success, even down to the number of garments on a clothesline on wash day, caused envy among many of the Indians. And considering the number of emigrants collecting at the mission, with too many white people onboard, there was little focus on the Indians themselves.

Dr. Whitman and Spalding also faced newly arrived thorns in their sides: Catholic priests in search of Indian converts. At one point, Whitman told the Cayuse he would leave should they wish to join the Catholics. They did not take him up on his offer.

Then the measles and dysentery struck. According to an estimate, the Cayuse lost at least 197 people, close to half of their total population.

Plus, they were likely aware of tribal die-offs downstream on the Columbia from previous incursions of the white man’s diseases. The Chinook, for example, who had been a major trading force when different Indian groups got together at The Dalles, had been virtually wiped out.

With these epidemics in mind, the Whitmans had long worried about how the Indians treated the ill. Obviously, overheating a victim in a sweat lodge followed by a quick run and a dip into frigid water would not fit into the doctor’s knowledge of good medicine.

Then there were the “te-wats,” or Indian medicine men. If someone died under one’s care, that meant death for the medicine man, too, carried out by the victim’s relatives. Everyone had heard of the death of some “te-wat” or another, and in some instances, Dr. Whitman was lucky enough to oversee a recovery. One, the aforementioned Stickus, had become a trustworthy friend. The Whitmans had taken him into their home, where both nursed him back to health.

Dr. John McLaughlin had pointed out Whitman’s precarious place among the Indians at the Hudson’s Bay Company post in Vancouver, but so far nothing had happened.

Therefore, it disturbed Dr. Whitman when two people, Father Brouillet and Chief Stickus, warned him of trouble brewing among the Cayuse. Drury felt Whitman believed he couldn’t leave the sick at the mission. Perhaps only he would be targeted.

He hoped that a nonconfrontational stance would quell the situation, as it had in an earlier experience, when a chief pulled his ear during a discussion.

True to his teaching, Whitman turned his “other cheek,” resulting in another ear-pull. The Indian then tore off his foe’s hat and flung it into the mud. Whitman retrieved it and set it back in place. Of course, it was then thrown down again. Whitman donned it once more, ending the confrontation as the chief departed in disgust. But rumors of poisoning Indians and sick children had not been part of that argument.

And so, Nov. 19, 1847, arrived. A steer was to be slaughtered. Therefore, when Indians began collecting in the mission yard, residents did not feel overly alarmed. A host of Cayuse men waited, wrapped in blankets against the cold.

Drury collected details about the Whitman massacre primarily from survivors’ eyewitness accounts, but years after the event, when they were older.

No one remembered how many Indians were involved, and no one mentioned any women in the group, perhaps to ameliorate the serious purpose of the men planning to attack. (Indian women are almost always left out of the author’s accounts, anyway.)

But the details of that dreadful day would prove unforgettable.