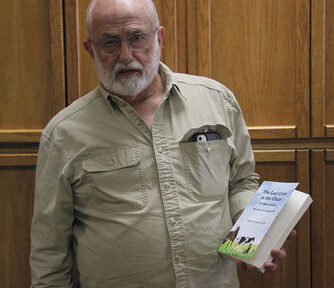

By D.E. Larsen DMV

Neurology, the study and treatment of disorders of the nervous system, in early-1970s veterinary medicine always seemed like a waste of time to me.

In school, we seemed to spend untold hours learning detailed anatomy of the brain and nervous system. We could intervene in some things, like spinal injuries. But the viral diseases of the brain and even the bacterial infections were tough nuts to crack.

It seemed that every neurologist loved his/her specialty. Polyradiculoneuritis would pop up somewhere, during every series of lectures. After spending the better part of an hour on the topic, the professor would note that most of us wouldn’t encounter a case in our lifetimes.

Why, then, do I have pages of notes on a disease I will probably never see? There would be virtually nothing I could do for a patient except provide competent nursing care and hope for recovery.

Of course, I had the notes because of the pending test. I always felt that it was a total waste of time.

In practice, I ventured into the brain only on rare occasions.

My first case was a necropsy on a cow that died suddenly during the morning milking.

In those days, I was a budding pathologist. I completed a very thorough necropsy, only to find absolutely no explanation for this death. The cow’s owner wanted an answer, and the only place I hadn’t looked was the brain. (I had spent the summer following my sophomore year in vet school working on the necropsy floor.)

Extracting the brain was an easy task. I skinned the head and then shaved the bone away from the brain with a small hatchet. A couple of snips at the dura and I lifted the brain from the skull.

Laying it on a board, I cut it in thick longitudinal layers. On the third slice, I hit a large pocket of mush. This cow had experienced a massive stroke. I offered to send the tissues for an accurate diagnosis, but the farmer was aware of our limitations.

“What are you going to do with any answer they give you?” he asked.

* * * * *

Then there was Buddy, a 12 week-old hound pup belonging to Frank Updegrave. I had seen Buddy a couple of times for routine vaccines and such.

On this day, Frank was helping a friend build a shed. They were putting up rafters as Buddy ran around doing hound stuff, nose to the ground as he followed some scent. Right about then, he was suddenly in the wrong place at the wrong time as one of the rafters fell from the top of the roof. The end landed on the front of his forehead. The two men gathered the dog up and came running to the clinic.

The top of Buddy’s skull was caved in, depressed into the brain, maybe an inch. The frontal sinuses were open. And worst of all, I could see brain tissue oozing into the wound.

After just a brief look, I took a deep breath and turned to Frank with an assessment.

“Frank, I don’t think I am going to be able to help him,” I said. “His skull is caved into his brain, and the frontal sinuses are open to the wound. The chances of saving this guy are slim, in fact, slim to none.”

“I know, but we have to try, Doc,” Frank replied. “Can you just try? I have total faith in your skills.”

In those days, we didn’t have specialty clinics on every corner. If this were going to get done, it would be by my hands.

“I will give it a try,” I said. “I will do everything I can. Just one thing, Frank: I want you to sign a euthanasia release before surgery. If things go from bad to worse, there is no reason to put Buddy through any discomfort by waking him up.”

Buddy was unconscious through the entire exam. I intubated him without induction drugs and used only halothane gas anesthesia. We shaved and prepped the wound, and reflected the skin edges from the bone. There was probably a two-inch square of skull bone depressed nearly an inch into the brain. Tissue was oozing around the edges. The break of the skull bone opened the upper corner of the frontal sinuses.

I was obviously beyond my experience base at this point. I used curved mosquito forceps to pry the depressed bone from the brain. I mopped up loose tissue and wondered what to do next.

There was a significant depression in the brain’s frontal lobes. I placed a couple of sutures in the dura mater, just enough to close the tear. Then I placed a couple of 22-gauge stainless steel sutures in the leading edge of the skull bone to maintain a substantial reduction.

The posterior portion of this bone was still attached. It was a jagged-enough leading edge to provide a reduction with adequate closure of the sinuses. I routinely closed the skin wound.

Then I unhooked Buddy from the gas. Now it was just a waiting game.

By the end of the day of surgery, Buddy was becoming responsive, acknowledging your presence, even raising his head a little. The next day, he was sternal but pressing his right side to the edge of his kennel. On the second day, he ate a few bites and walked as long as he had a wall to press against his right side. This meant he could move, but only in a counterclockwise direction around the room. After another couple of days, we sent Buddy home. He could walk without a wall and was improving every day.

The following summer he came in for his annual exam. I glanced out into the waiting room. Frank, a tall, lanky young man who might have been a couple of years out of high school, was sitting with Buddy, by then a full-grown hound, taking up his entire lap, a forever puppy. He was pretty functional, but he never progressed beyond his 10- or 12-week-old mental abilities.

* * * * *

It was maybe a couple of years after Buddy’s accident that Sally Smith brought her Australian shepherd, Sport, for an exam.

Sally was a smaller blonde woman in her early 40s, very athletic. She had purchased the BeBee brothers ranch in Liberty, where she ran emus. Sport was a cow dog who only had birds to herd.

During the exam, he displayed a lot of anxiety. It was apparent that he knew things weren’t right. His reflexes were impaired. He could barely walk. Sally said he seemed to worsen by the hour. My first concern was rabies, but his vaccination was current. Sally agreed to leave him overnight for observation and treatment.

I was at a loss for a diagnosis. I started Sport on some trimethoprim/sulfa and some dexamethasone to cover bases. The trimeth/sulfa would treat toxoplasmosis specifically and would also cover most bacterial infections of the central nervous system. The steroid would reduce CNS swelling. We would have to see what morning would bring.

By morning he was completely paralyzed, flat out. He could not raise his head but was bright and alert, following my every move with his eyes. He could lap water and eat with assistance. Without a diagnosis, I was dead in the water to provide a prognosis, but things were looking pretty bleak.

Sally came in later that morning, and I accompanied her back to the kennel, where Sport lay with his eyes dancing, mouth open and tongue lapping. The tip of his tail still had a slight wag. I knelt and patted his head. Then I noticed a large scratch across its top.

“That’s quite a scratch,” I said.

“Oh yes, That is probably from a raccoon. Buddy is out hunting those things every night,” Sally replied.

I stood up and looked at her.

“Raccoons,” I said.

“He runs them all night long and often tangles with them,” she said. “He killed a big old boar the other night.”

I knelt and scratched Sport on the head, thinking, “Wow, polyradiculoneuritis.”

“Don’t you believe it!” I told myself. “I’ll be damned. Buddy, you have coonhound paralysis!”

Apparently, I had spoken a little louder.

“What did you say?” Sally asked.

“This is coonhound paralysis,” I replied. “It is a rare disease in dogs, very similar to Guillain-Barre syndrome in man. We don’t know what causes it, but it is most often associated with contact with raccoon saliva, hence, coonhound paralysis.

“There is not much to do for him except to provide nursing care. It will get worse; all his muscles will atrophy. But if his respiratory muscles remain functional, there is a chance that he will recover and return to normal. We can care for him here if you like, but the expense may be high.”

“I will take him home and make a bed for him behind the stove. He will be much happier at home,” Sally said.

“Make sure his bed is well-padded, turn him often, several times a day, and help him with food and water,” I replied. “We will try to keep track of things with you but call if you have any questions.”

It was several months before I saw Sport again. He was pretty much back to normal. Sally said he was looking bad after a couple of weeks of paralysis but then slowly returned. Now he was chasing those darn raccoons again.

About two years later, Sport was in the clinic with another onset of paralysis. Things went about the same as his initial episode. The neurologists in school had always said it would be a once-in-a-lifetime diagnosis.

I would guess that I must have lived a couple of lifetimes. The diagnosis was made twice but to the same patient.

– David Larsen is a retired veterinarian who practiced 40 years in Sweet Home. More of his stories are available on his blog at docsmemoirs.com.